Frequently Asked Questions

About Us

-

1. What is KICLEI Canada?

KICLEI Canada is a non-partisan, citizen-led initiative that supports local communities in reclaiming decision-making authority from top-down global programs. We equip Canadians with research, tools, and training to help councils evaluate and, where needed, reject external climate frameworks that may compromise local autonomy.

What does “KICLEI” stand for?

KICLEI is an independent watchdog initiative, modeled after ICLEI (International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives), but focused on localism over globalism. While ICLEI promotes UN-aligned climate programming, KICLEI supports locally led, transparent governance that puts Canadian communities and municipal priorities first.

Is KICLEI affiliated with a political party?

No. KICLEI is non-partisan and receives no funding from political parties, governments, or corporations. We are funded entirely by private Canadian citizens through memberships, donations, and volunteer contributions. This independence allows us to remain fully accountable to the people we serve.

What is KICLEI’s mission?

To support Canadians in reclaiming local governance, protect democratic processes, and promote practical, community-driven solutions—without the pressure of foreign or ideological influence.

What does KICLEI actually do?

Provides research reports, council-ready resolutions, and local governance templates

Hosts public webinars, Zoom strategy calls, and town hall sessions

Equips residents with facts, tools, and training for civic engagement

Supports local leaders and community organizers

Promotes alternatives to UN-aligned programs like the PCP and ICLEI

Who founded KICLEI?

Maggie Hope Braun founded KICLEI after years of experience in ecosystem management and community organizing. Her work is focused on empowering Canadians to defend sovereignty through informed local action.

What has KICLEI accomplished so far?

Thorold withdrew from the PCP program

Tiny Township launched a PCP cost review

Renfrew County requested a CO₂ sequestration report

Lethbridge reduced its net-zero target, saving millions

Rural municipalities are beginning to opt out of urban-centric programming

Dozens of councils have received briefings, with many now questioning the PCP’s costs and implications

How can I get involved?

Join our network and stay informed

Subscribe to newsletters (Gather 2030 + KICLEI on Substack)

Join a Zoom call in your area or across Canada

Attend council meetings and raise awareness respectfully

Donate or become a member to support our mission

How do I contact KICLEI?

You can reach out to Maggie Hope Braun and the KICLEI team through the Contact Form on our website. We’re happy to help support your local advocacy efforts.

-

What is KICLEI’s approach to advocacy?

KICLEI promotes respectful, evidence-based, and non-confrontational advocacy. We believe that engaging with local councils must be done with professionalism, clarity, and emotional intelligence — not through protest or pressure tactics. Our goal is to support informed decision-making, not demand outcomes.

How does KICLEI engage with municipal councils?

KICLEI equips residents and delegates with:

Research reports and council-ready templates

Strategic coaching via Zoom calls

Clear, constructive messaging tools

Support for respectful public engagement at council meetings

We encourage collaborative dialogue — not confrontation — to foster long-term trust and transparency between residents and elected officials.

Does KICLEI support protests or disruptions at council meetings?

No. KICLEI strictly adheres to municipal codes of conduct and discourages any form of disruptive behavior. This includes shouting, profanity, signage without approval, or emotionally charged outbursts. Our supporters are expected to represent the initiative with professionalism and respect at all times.

What kind of communication does KICLEI recommend?

All public communication — whether it's a letter to council, email, media interview, or town hall presentation — should be:

Clear and solution-oriented

Respectful in tone

Focused on local facts and impact

Free from speculation, personal attacks, or hostile language

What issues does KICLEI focus on?

KICLEI focuses on local issues with national relevance, including:

The cost and implications of climate programs like PCP

Transparency in municipal policy adoption

Impacts of land-use regulations on property rights

The role of global frameworks in shaping local decisions

Practical, locally driven alternatives to net-zero mandates

What principles guide KICLEI’s advocacy work?

Our team and community follow these principles:

Respect for local autonomy

Truthfulness without hostility

Clear and jargon-free messaging

Commitment to community-first solutions

Celebrating small wins and strategic patience

Preparedness and professionalism at all public appearances

What happens if someone doesn't follow KICLEI's code of conduct?

While we are not a membership-based organization with enforcement powers, we do take our credibility seriously. Anyone acting in ways that contradict our mission may be:

Provided guidance on aligning with our values

Formally dissociated from KICLEI communications or events

We aim to maintain a high standard of trust and reliability with municipalities and communities alike.

How can I represent KICLEI at a council meeting?

Here’s a quick checklist for being an effective delegate:

Stay calm, confident, and respectful

Dress professionally and speak clearly

Reference reports or materials submitted in advance

Focus on facts and local solutions

Stick to your allotted time

Avoid reacting emotionally, even under pressure

Be available to answer questions or follow up later

A strong presence from informed residents can go a long way in opening the door to policy reconsideration.

What’s the key to KICLEI’s advocacy success?

Tone, timing, and truth. Our approach has influenced real policy shifts because we present credible, well-researched alternatives and communicate them respectfully. Change takes time — but it starts with local engagement done right.

-

Local Priorities vs. Global Agendas

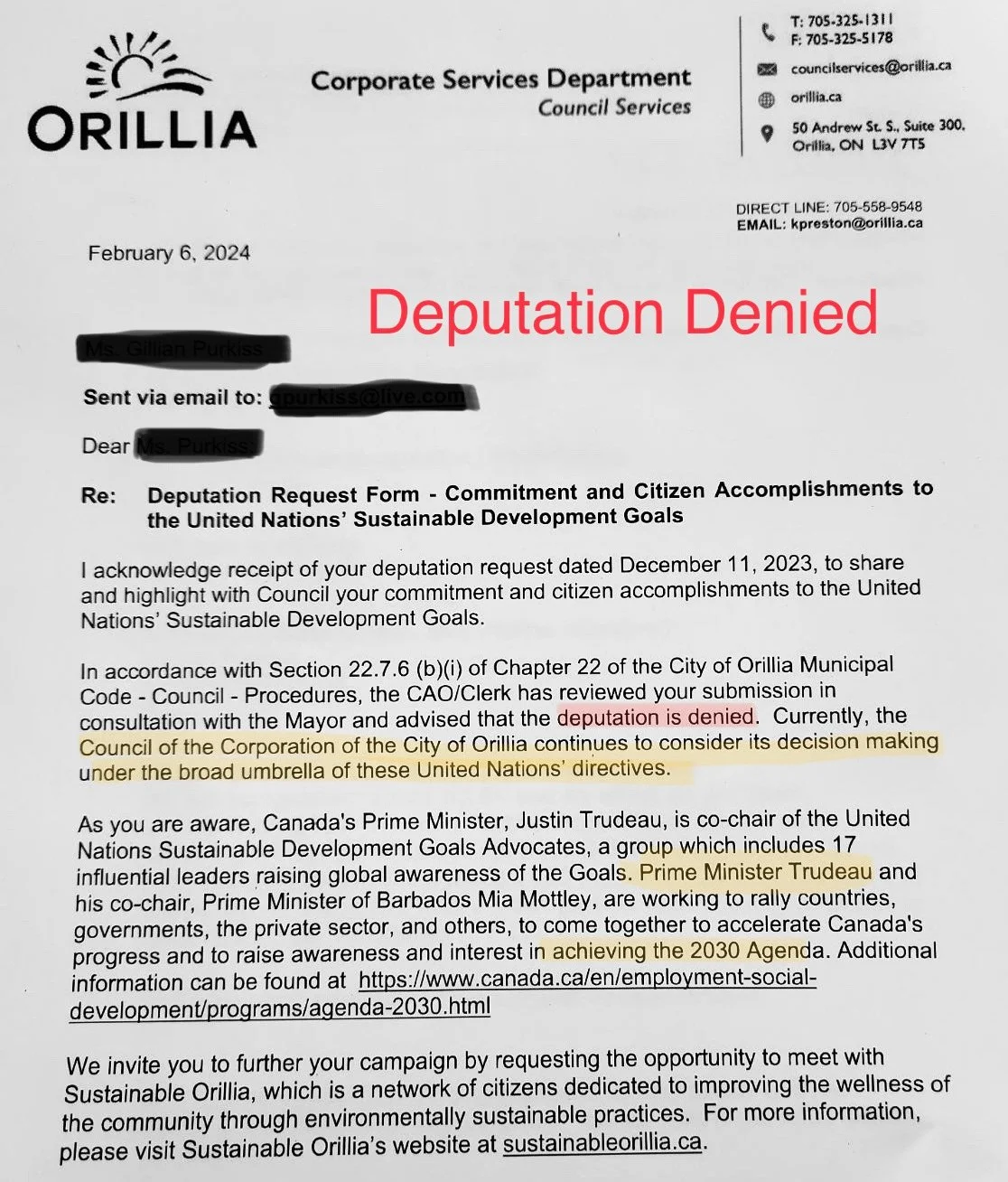

Global frameworks like Agenda 21, the Paris Agreement, and the Sustainable Development Goals are drafted by international bodies and implemented by unelected NGOs. They often do not reflect the needs, challenges, or opportunities of individual Canadian communities. Localism ensures that policies are grounded in lived realities, not distant agendas.Protecting Democratic Accountability

When councils adopt UN-aligned programs through ICLEI or FCM, they risk bypassing public consultation. Most residents — and even many councillors — are unaware of the long-term commitments embedded in “voluntary” climate programs. Localism restores accountability by making sure decisions are debated openly, transparently, and with resident input.Fiscal Responsibility

Global mandates frequently demand costly investments in technologies and infrastructure, while offering little measurable local benefit. Localism prioritizes affordability, ensuring taxpayer dollars fund projects that serve communities directly rather than corporate or international interests.Building on Natural Strengths

Canada’s vast forests, wetlands, soils, and agricultural lands already make the country a carbon sink. Local communities are best positioned to steward these assets, using them as a foundation for practical climate resilience — rather than ignoring them in pursuit of arbitrary global targets.Resilience Through Self-Reliance

Communities that focus on adaptation, self-sufficiency, and local decision-making are more resilient in the face of change. Whether preparing for floods, wildfires, or shifting markets, localism ensures solutions are flexible, cost-effective, and tailored to real needs.The Path Forward

Reform organizations like FCM so they return to their founding mission of amplifying municipal voices to the federal government — not embedding UN frameworks in local policy.

Encourage councils to adopt resolutions that reaffirm sovereignty over local decision-making.

Promote genuine environmental stewardship rooted in adaptation, local carbon sinks, and fiscal responsibility.

Localism does not mean isolation. It means communities lead with their own priorities, collaborate on their own terms, and refuse to cede control to unelected global bodies.

Who is Influencing Municipal Councils?

-

ICLEI’s UN Origins ICLEI — originally the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives — was established in 1990 at the World Congress of Local Governments for a Sustainable Future, held at the United Nations headquarters in New York. Its founding mission was explicit: “Local governments must begin to restructure social and economic life at the local level.” Today, ICLEI brands itself as “Local Governments for Sustainability,” but its mission continues to align with global UN frameworks including Agenda 21, the Paris Agreement, and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

ICLEI was not formed by Canadian municipalities. It is a United Nations-created NGO with Special Consultative Status at the UN Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), acting as the UNFCCC’s designated representative body for local governments worldwide. Its core mandate is to implement global climate directives at the local level.

Canada Office Structure ICLEI Canada operates as a country office within the global ICLEI network. Its legal registration as a nonprofit in Ontario does not negate its status as part of an international NGO network. The ICLEI Charter (2021) confirms that national offices, like Canada’s, are authorized and governed under the global structure headed by the World Secretariat in Bonn, Germany.

Requests for an organizational chart, governance structure, and funding breakdowns from ICLEI Canada have been submitted multiple times by citizens and councils. As of this writing, ICLEI has never responded.

Role in Global Sustainability Agenda ICLEI’s role is to “translate” international sustainability mandates into local climate frameworks. This includes:

Embedding global targets (such as net-zero by 2050) into municipal policy

Advising cities on emissions inventories and carbon budgeting

Promoting smart city infrastructure, green energy procurement, and land-use reforms

Encouraging climate emergency declarations and local action plans modeled on UN frameworks

ICLEI also engages in partnerships with major corporations, international banks, and global NGOs — many of which have commercial interests in renewable energy, smart infrastructure, or ESG-compliant investments.

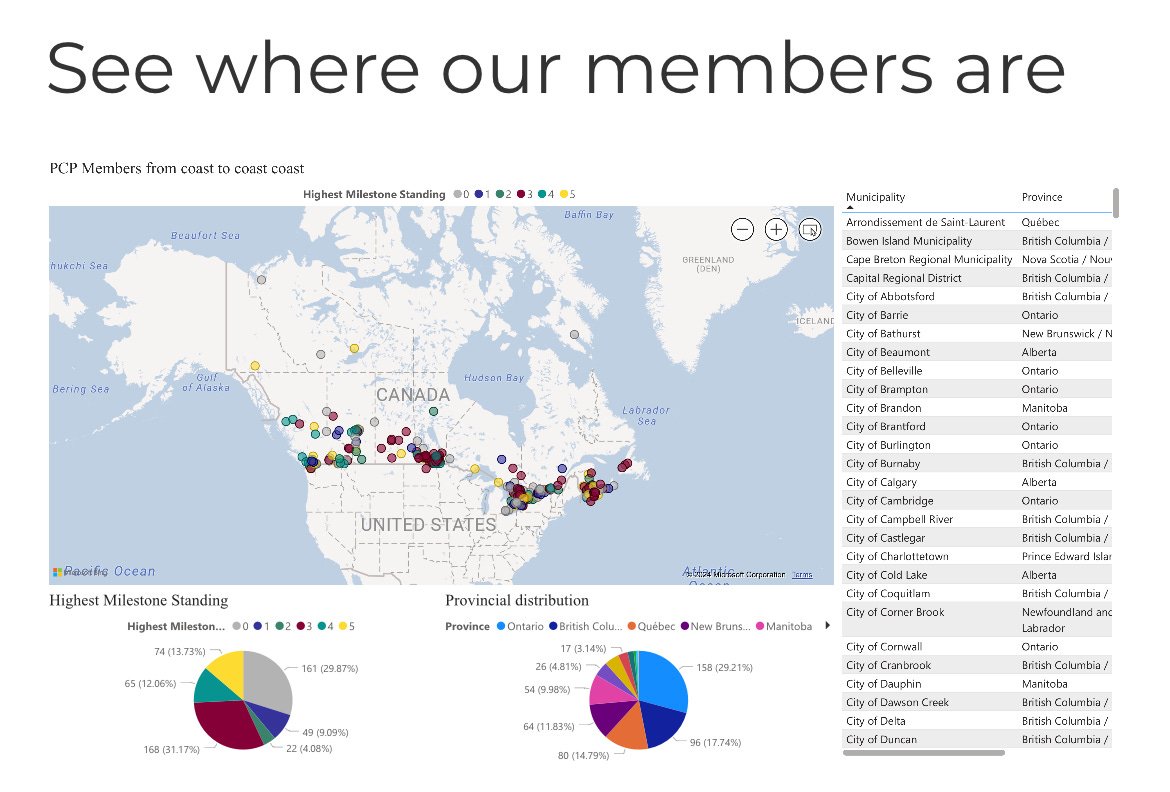

ICLEI’s Co-Administration of the PCP In Canada, ICLEI co-administers the Partners for Climate Protection (PCP) program alongside the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM). When a municipality joins the PCP, it agrees to a five-milestone process that includes emissions inventory, target-setting, action plan development, implementation, and reporting.

Although PCP is widely described as “voluntary,” many municipalities treat the commitments as binding once passed. ICLEI helps design these frameworks and often works with municipal staff to shape policies that influence buildings, transportation, procurement, and permitting systems — without direct voter involvement.

Funding and Conflict of Interest Concerns ICLEI receives funding from international foundations, government grants, and corporate partners — including Google.org, Wawanesa, Co-operators, and Canada Infrastructure Bank. Many of these partners benefit financially from the technologies and services municipalities are encouraged to adopt.

Notably, ICLEI received a $4 million funding partnership with Google to drive data-driven climate initiatives. This raises critical questions about data harvesting, municipal surveillance, and the influence of private sector actors on local public policy.

Requests for a breakdown of ICLEI’s revenue sources, funding conditions, and potential conflicts of interest have gone unanswered.

Unanswered Questions and Public Transparency Despite numerous open letters and council inquiries, ICLEI has never directly answered the following:

Why do so few Canadian councillors know about ICLEI, even when they adopt PCP?

Why is ICLEI not named in key council reports, despite being a co-administrator of the PCP?

Why did ICLEI create a “misinformation” webpage rather than respectfully respond to public questions?

Why has ICLEI never provided a formal response to open letters submitted by Canadian citizens and councils?

Until these questions are answered transparently and in writing, Canadians are left with serious concerns about the legitimacy, accountability, and influence of ICLEI in Canadian municipal governance.

Suggested Transparency Questions for Councils to Ask ICLEI or Staff:

Who is ICLEI, and what is its full organizational structure?

Who funds ICLEI Canada, and are any funding sources tied to corporate interests?

Has ICLEI ever received funding or in-kind support from Google, BlackRock, or other multinational firms?

Why does the PCP program not disclose ICLEI’s role explicitly to councils before adoption?

Does ICLEI collect or access local emissions data from municipalities?

Does participation in PCP create any obligations under international treaties?

Has ICLEI responded to community letters or media requests?

Note: Some information in this section cannot be fully confirmed due to ICLEI’s ongoing refusal to answer questions submitted by the public, councils, or independent researchers. This lack of transparency should be a key point of concern for any community considering PCP participation or ICLEI partnership.

-

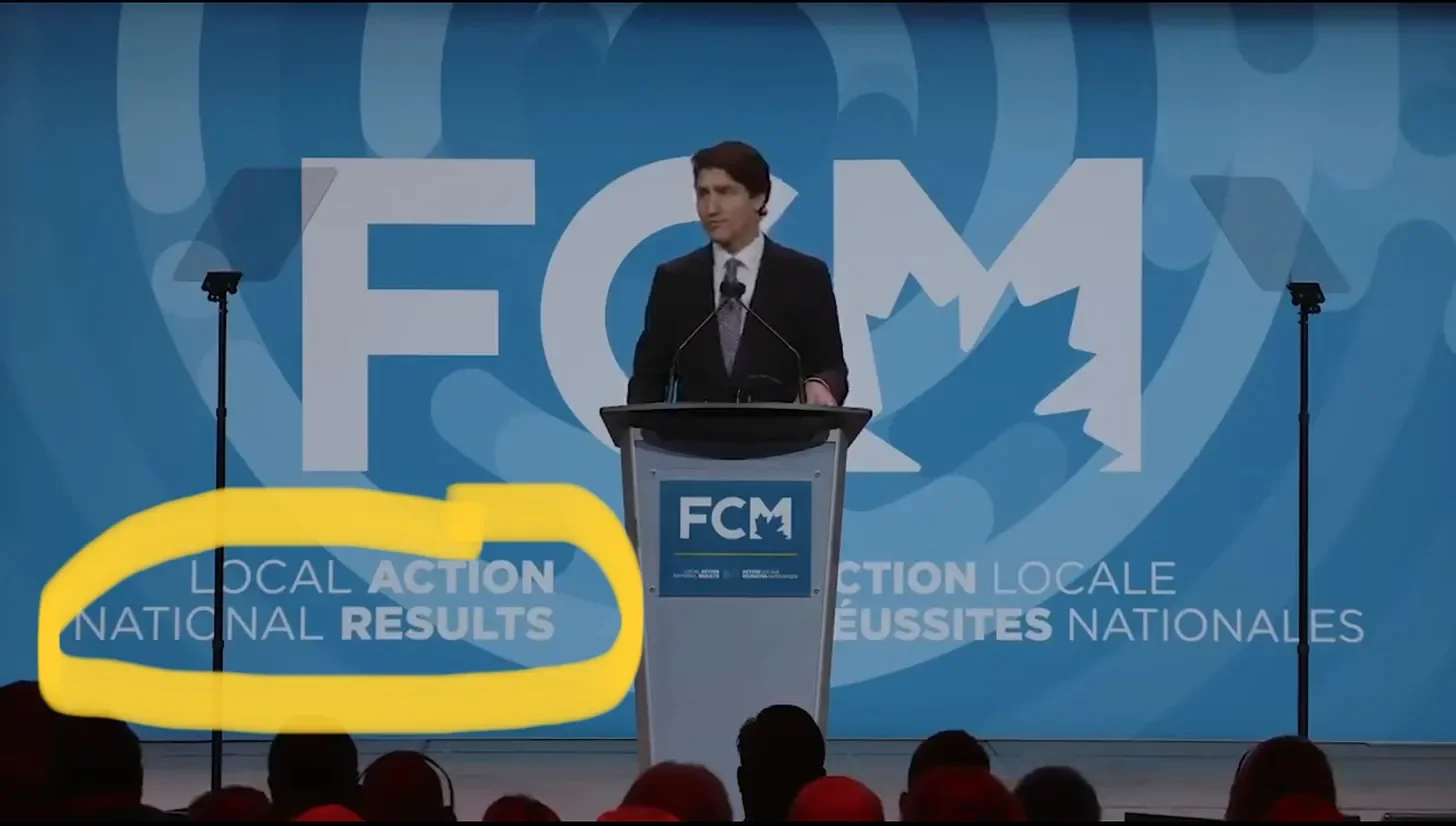

What is the FCM?

The Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) is a national organization representing cities and towns across Canada. Founded in 1901 (as the Union of Canadian Municipalities, later merging with the Dominion Conference of Mayors), its original mandate was to lobby the federal government on behalf of municipalities for fair funding and infrastructure support.What role did FCM play in Agenda 21 and the UN Earth Summit?

In the early 1990s, FCM became a key participant in the UN’s Preparatory Committee (PrepCom) process leading up to the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. According to FCM’s own UNCED Primer:Canadian municipalities, with strong leadership from Montreal, directly helped draft Agenda 21, the UN’s blueprint for sustainable development.

This involvement positioned FCM not just as a lobby group, but as a co-author of global sustainability frameworks that still shape municipal policy today.

How has FCM’s role changed since then?

Historically, FCM advocated upwards to Ottawa on behalf of local governments. Today, much of its work flows downwards—delivering federal and UN-aligned policies into municipalities through funding programs and climate frameworks.In 1994, FCM partnered with ICLEI to launch the Partners for Climate Protection (PCP) program as a direct follow-up to Agenda 21.

FCM administers the Green Municipal Fund (GMF), which Ottawa has endowed with over $1.65 billion since its creation. GMF explicitly supports projects tied to federal net-zero goals and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

What is the GMF?

The Green Municipal Fund is a federally financed fund managed by FCM. Municipalities apply for funding to support projects such as energy retrofits, electric fleets, climate action plans, and “net-zero communities.”While GMF money originates from federal tax dollars, its administration through FCM removes direct parliamentary oversight.

To access GMF funding, municipalities are typically expected to participate in PCP or other FCM climate programs, meaning that dollars are tied to policy commitments.

Why does this matter?

This structure effectively makes FCM the gatekeeper of federal climate-related funding for municipalities. Instead of offering municipalities direct support with no strings attached, federal money is funneled through an NGO that conditions access on compliance with global climate frameworks. This shift has transformed FCM from a local advocate into an implementation partner for federal and UN agendas.A Call for Reform

Member municipalities have the power to make resolutions at FCM conventions. If enough councils speak up, they can demand a return to FCM’s original purpose: advocating for municipalities to Ottawa, not enforcing Ottawa’s (or the UN’s) agenda on municipalities.Possible reforms include:

Restoring Advocacy: Refocus FCM on lobbying for municipal priorities—like infrastructure, housing, and services—without imposing external policy frameworks.

Funding Transparency: Ensure federal dollars administered by FCM (like GMF) are distributed fairly, without mandatory climate policy conditions attached.

Member Accountability: Require FCM leadership to be directly accountable to its municipal members, with clear transparency on outside partnerships and funding sources.

Alternative Representation: If reform is blocked, municipalities may need to explore creating a new organization to replace FCM as a true grassroots advocate for local governments.

-

Canada’s Flagship Net-Zero Framework

The Partners for Climate Protection (PCP) program, co-administered by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) and ICLEI Canada, is presented as Canada’s flagship municipal climate initiative. Its five-step “milestone framework” mirrors international net-zero programs worldwide, making it in effect a mini Paris Accord for any municipality that commits.While marketed as free and voluntary, PCP is structured to guide municipalities into long-term obligations—often without transparent discussion of costs, benefits, or alternatives.

The Real Cost of PCP

PCP functions much like a freemium business model. Signing up is simple: councils pass a short resolution and notify FCM. But after entry, the program demands increasingly costly commitments.Milestone 1: Baseline emissions inventory – requires significant staff time, software, and technology.

Milestone 2: Target setting – councils impose self-obligations that are then used to justify ongoing spending.

Milestones 3–4: Action plan and implementation – often involves costly technology purchases, building retrofits, EV infrastructure, densification policies, and “smart city” initiatives.

Milestone 5: Monitoring and reporting – locks councils into perpetual data collection and compliance cycles.

The real trap is that municipalities are told the program is free, but every milestone requires new expenditures—diverting tax dollars away from local priorities.

Disclaimer and Liability

Despite being federally financed, the PCP program carries an explicit disclaimer:“This project was carried out with assistance from the Green Municipal Fund, a Fund financed by the Government of Canada and administered by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, and from ICLEI – Local Governments for Sustainability (Management) Inc. Notwithstanding this support, the views expressed are the personal views of the authors, and ICLEI Canada, the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, and the Government of Canada accept no responsibility for them.”

This creates several governance concerns:

No Accountability – Program administrators refuse liability for recommendations or outcomes.

Taxpayer-Funded, Risk Localized – Federal funds flow through GMF, but local councils bear the costs and risks.

Hidden Legal Exposure – Councils assume obligations under PCP while its designers disavow responsibility.

If PCP, ICLEI, and FCM are confident in their framework, why disclaim responsibility for it?

Connection to the Green Municipal Fund (GMF)

The GMF, a multi-billion-dollar “green infrastructure” fund financed by the federal government and administered by FCM, is tightly linked to PCP. Councils are told PCP participation makes them more competitive for GMF grants. This effectively ties municipal access to federal funding to alignment with ICLEI/FCM climate policies, reducing autonomy and pressuring councils into participation.The Bigger Picture

PCP has been in operation since 1994, yet no comprehensive cost assessment has ever been undertaken.

Net-zero frameworks like PCP ignore pre-existing carbon sinks—a major gap discovered and exposed by KICLEI.

Councils often commit without public consultation, economic review, or clear disclosure of long-term obligations.

A Smarter Approach for Councils

Recognize that PCP is voluntary—withdrawal is as simple as rescinding the joining resolution and notifying FCM.

Conduct local cost-benefit analyses before committing tax dollars.

Focus on adaptation strategies (infrastructure resilience, flood mitigation, regenerative land management) instead of top-down mitigation frameworks that ignore Canada’s unique context as a vast carbon sink with minimal global emissions share.

Science Behind the Debate

-

The Partners for Climate Protection (PCP) joining resolution includes a “Supporting Rationale” that claims:

Climate change is increasing extreme weather events (fires, floods, droughts, rising seas).

The Paris Agreement requires local action to prevent severe climate impacts.

Municipalities influence 50% of Canada’s emissions, so net-zero policies are presented as essential.

Climate investments will also deliver co-benefits such as resilience, public health, and lower costs.

Because this rationale is built directly on contested climate claims, councils are effectively being asked to adopt sweeping net-zero commitments on the basis that:

Human emissions are the primary driver of recent warming.

Extreme weather is increasing because of climate change.

Municipalities are a critical lever for national and global climate goals.

KICLEI addresses these claims not to deny climate change, but to:

Clarify what is settled science versus what remains debated or overstated.

Highlight Canada’s unique carbon sink reality and small share of global CO₂.

Show that many PCP-aligned climate policies are disproportionate to the actual risk and may divert resources from more effective adaptation.

In the following subsections, we respond to the resolution’s supporting rationale with evidence-based analysis:

Voluntary nature of Agenda 21 & PCP — there is no binding municipal obligation.

Canada’s carbon sink context — large natural sequestration offsets emissions.

The logarithmic effect of CO₂ — diminishing warming potential.

Historical climate variability — warming and cooling are not new.

Consensus science debates — 0.3% vs 97% methodologies explained.

Extreme weather trends — deaths down, costs up due to exposure, not hazard frequency.

CO₂ as “pollutant vs. plant food” — reframing the role of carbon dioxide.

Together, these points demonstrate why local governments should carefully reconsider whether the PCP rationale truly justifies long-term, costly net-zero programs.

-

Climate Science & Extreme Weather: Responding to the PCP Rationale

The PCP resolution’s “Supporting Rationale” rests on several key claims: that climate change is increasing extreme weather, that municipalities are responsible for half of Canada’s emissions, and that local net-zero policies are essential to meeting Canada’s Paris targets. Below, we address each of these points in turn, with evidence that challenges their use as blanket justification for costly municipal climate programs.

Extreme Weather Trends

Disaster costs have risen largely due to population growth, urban expansion, and asset concentration in vulnerable areas—not because hazards themselves are increasing in frequency or intensity.

Mortality from disasters has declined worldwide thanks to better infrastructure, forecasting, and preparedness.

The IPCC itself acknowledges regional complexity: some areas see heavier rainfall, while others show no long-term increase in hurricane or tornado frequency.

Scientific Consensus: 0.3% vs. 97%

Cook et al. (2013) arrived at 97% by including any paper that mentioned human influence, even indirectly.

Legates et al. (2013) found that only 0.3% of papers explicitly said humans are the primary cause of recent warming.

The difference shows a methodological artifact: consensus is often overstated when broad definitions are used.

CO₂’s Role in Warming

CO₂ is a greenhouse gas, but its effect is logarithmic: each doubling has a diminishing impact on warming.

Human emissions account for ~4% of total CO₂ entering the atmosphere annually; Canada accounts for ~1.6% of that.

This means Canada’s share of global atmospheric CO₂ is statistically negligible—yet PCP treats municipal reductions as globally decisive.

Canada’s Carbon Sink Reality

Canada’s forests, wetlands, and agricultural soils absorb vast amounts of CO₂ annually, making many regions net carbon sinks.

Programs like PCP do not count these pre-existing sinks when setting net-zero targets—one of KICLEI’s key discoveries.

Councils should request carbon stock data from GIS departments and compare annual sequestration to emissions before committing to mitigation.

Historical Climate Variability

Climate has shifted naturally for millennia (e.g., Medieval Warm Period, Little Ice Age).

Local adaptation to natural variability—like flood management, infrastructure resilience, and rotational grazing—may offer more benefits than costly global mitigation frameworks.

Voluntary Nature of Agenda 21 & PCP

Neither Agenda 21 nor the Paris Agreement binds municipalities to emission targets.

PCP is a voluntary framework; municipalities can join or withdraw by council resolution.

Councils should weigh costs against benefits and not assume participation is mandatory.

Summary:

The PCP rationale overstates the role of local governments in preventing global climate change. Extreme weather trends are more socio-economic than climatic, Canada’s net emissions are small in the global context, and existing natural sinks already offset much of what we emit. Municipalities should prioritize adaptation and evidence-based stewardship rather than adopting costly, top-down mitigation programs designed without regional context. -

This claim is widely repeated in media and policy circles, but the data tells a more complex story.

What the Data Shows

The IPCC itself has stated that there is low confidence in any global increase in frequency or intensity of most extreme weather events (hurricanes, tornadoes, floods) over the past century.

Some regional trends exist (for example, heavier rainfall in certain areas), but globally the evidence of increased disasters linked directly to CO₂ is weak.

Disasters vs. Hazards

A hazard (storm, flood, wildfire) only becomes a disaster when it impacts human settlements or infrastructure.

Reported “disaster losses” have increased largely because:

More people are living in high-risk areas (coastlines, floodplains, wildfire zones).

Infrastructure and assets are more valuable today, so damages cost more.

Global reporting systems now record more events than in decades past.

Insurance Costs & Market Exits

Rising insurance premiums in some regions are often presented as proof of worsening weather.

In reality, insurers price based on exposure (population + assets at risk), not just hazard intensity. More expensive homes in risky areas = higher payouts.

Long-Term Death Trends

Historical data shows that deaths from natural disasters have plummeted over the last century, thanks to better infrastructure, early warning systems, and emergency response.

Even if certain hazards become more intense, societies are far less vulnerable than before.

Why This Matters for Local Policy

Canadian municipalities are being asked to adopt costly PCP-aligned mitigation projects on the basis that disasters are worsening. But:The evidence does not show a global spike in disasters caused by CO₂.

Local resilience (adaptation measures like flood prevention, fire breaks, and strong infrastructure) delivers direct, measurable benefits.

Spending millions on mitigation to “prevent” disasters has no guarantee of success, while adaptation directly protects communities.

Are Natural Disasters Increasing Because of Climate Change? (Part 2)

Hazards vs. Disasters

A hazard is a natural event (e.g., hurricane, wildfire, flood).

A disaster occurs when that hazard intersects with people, property, or infrastructure. More people and higher-value assets in risky areas make disasters costlier — even if the hazard itself hasn’t become more frequent or severe.

What the Data Shows

Deaths are down: Over the past century, deaths from natural disasters have plummeted thanks to better infrastructure, emergency response, and forecasting.

Costs appear up: Economic losses have risen, but this is largely because we build more expensive infrastructure in vulnerable areas (coastal cities, floodplains, forests).

Mixed evidence on frequency and intensity: Some events, like heavy rainfall, show regional increases. Others, like tornadoes and major hurricanes at landfall, do not show a consistent global upward trend.

Why Insurance Premiums Are Rising

Insurers leaving high-risk markets doesn’t automatically prove climate disasters are increasing. Often, it reflects greater exposure (more people and assets in harm’s way) rather than worsening hazards.

Peer-Reviewed Perspectives

Roger Pielke Jr., Bjorn Lomborg, and other researchers argue that normalized data (adjusted for GDP, inflation, population) shows no clear global trend in rising disaster frequency or intensity.

The IPCC itself acknowledges complexity — with regional variation rather than a universal surge in extreme weather.

Local Implications

Municipalities are often told climate change is driving a wave of disasters, justifying costly net-zero policies.

In reality, many risks can be mitigated more effectively through local adaptation:

Limiting development in floodplains

Building stronger infrastructure

Improving forest management and fire breaks

Strengthening emergency response systems

KICLEI’s Position

Disasters are real and preparedness is essential — but attributing every loss to CO₂ oversimplifies the issue.

Local resilience measures deliver far more benefit to Canadian communities than trying to “solve” global CO₂ levels through municipal net-zero spending.

-

CO₂ vs. Actual Pollutants

Real pollutants include sulfur dioxide (SO₂), nitrogen oxides (NOₓ), particulate matter (PM2.5/PM10), and ground-level ozone (O₃). These directly harm human health, cause smog, or damage ecosystems even at small concentrations.

Carbon dioxide (CO₂) is a colorless, odorless gas essential to life on Earth. It is the raw material for photosynthesis and therefore the foundation of the food chain.

CO₂’s Role in Climate

CO₂ is a greenhouse gas, meaning it contributes to trapping heat in the atmosphere.

Its warming effect is logarithmic — each additional molecule has a smaller impact than the last. This means that while CO₂ influences climate, the incremental effect diminishes at higher concentrations.

CO₂ as Plant Food

Higher CO₂ concentrations enhance plant growth, water efficiency, and crop yields (known as the CO₂ fertilization effect).

Satellite data shows a “global greening” effect over the last several decades, partly due to rising CO₂.

Some studies note that nutrient uptake can lag under elevated CO₂, but healthy soils and regenerative practices can offset this.

Why This Matters for Net Zero

Labelling CO₂ as a pollutant frames it as inherently harmful, ignoring its biological role and benefits to agriculture.

Net-zero frameworks often dismiss or undervalue land-based carbon sequestration methods (like rotational grazing, regenerative agriculture, and wetland restoration), even though these approaches are cost-effective and enhance CO₂’s positive role in ecosystems.

KICLEI’s Key Discovery

Most net-zero programs, including PCP, do not account for pre-existing carbon sinks such as forests, soils, and wetlands that already absorb massive amounts of CO₂ annually. Councils are therefore being asked to cut emissions without considering the natural balance already present in their regions.Policy Implication

Rather than treating CO₂ as a pollutant to be eliminated at any cost, municipalities should:Recognize the role of natural ecosystems as carbon sinks.

Focus on stewardship of forests, soils, and wetlands.

Invest in adaptation and local resilience rather than costly mitigation projects that provide little additional benefit in the Canadian context.

-

How much does Canada contribute to global CO₂?

Canada accounts for about 1.5–1.6% of global CO₂ emissions. Human-made CO₂ is roughly 4% of the total 0.04% atmospheric CO₂, meaning Canada’s share of the atmosphere’s CO₂ is only about 0.0006%. This is an extremely small fraction globally.Does Canada act as a carbon sink?

Yes. Canada’s vast forests, wetlands, and soils absorb more CO₂ than many regions emit. Studies (Kurz et al. 2008; Stinson et al. 2011) show Canadian forests sequester significant amounts of carbon, offsetting much of the country’s emissions.Do net-zero programs account for these sinks?

No. One of KICLEI’s key discoveries is that programs like PCP do not recognize pre-existing carbon sinks in their calculations. Municipalities are forced to count emissions, but not the carbon absorbed annually by their ecosystems. This makes regions that are already net carbon neutral appear as if they are polluters, pushing them into costly “mitigation” programs that are unnecessary.Why does this matter for councils?

If a municipality is already located in a net carbon sink region, its effective emissions are near zero. Yet PCP frameworks still require spending on emissions reduction technologies, building retrofits, and carbon reporting systems. This mismatch inflates costs without recognizing the natural sequestration that already exists. -

Does CO₂ cause warming?

Yes. It is well established that CO₂ has a greenhouse effect. The question is not whether it warms, but how much.Is CO₂’s warming effect unlimited?

No. CO₂’s influence on temperature is logarithmic, not linear. This means:The first increments of CO₂ cause the most warming.

Each additional unit has less impact than the last.

As concentrations increase, the incremental effect diminishes.

What does this mean for today’s policies?

Pre-industrial CO₂ levels were about 280 ppm.

Today, levels are around 420+ ppm.

Much of the strongest warming effect has already occurred.

Future increases in CO₂ will still have an effect, but a smaller, diminishing one.

Why is this important for Canada?

Since Canada’s share of global emissions is already tiny, and since additional CO₂ has diminishing warming potential, the cost of drastic net-zero policies may far outweigh the actual climate impact. -

Has Earth’s climate always changed?

Yes. Long before industrial activity, Earth experienced significant natural climate variability. Examples include:Medieval Warm Period (approx. 950–1250 AD) – a time when Europe experienced milder temperatures.

Little Ice Age (approx. 1300–1850 AD) – a colder period that impacted agriculture, settlements, and human survival.

What caused these changes?

These shifts were driven by natural factors such as solar activity, volcanic eruptions, and ocean circulation patterns—not modern industrial emissions.Why does this matter for Canadian municipalities?

It shows that climate change has always been part of Earth’s natural system.

Local governments should plan for adaptation (flood control, resilient infrastructure, water management) rather than assume emissions reductions alone will control future conditions.

Both warming and cooling phases bring challenges and benefits—for example, longer growing seasons in some regions, but also risks of flooding or drought in others.

What is the KICLEI position?

Adaptation strategies should be prioritized over costly, net-zero mitigation programs.

Councils should prepare for both possibilities—warming and cooling—given Earth’s history of fluctuating climate.

-

This question often comes down to how “consensus” is defined.

Cook et al. (2013): The 97% Claim

Cook’s team reviewed 11,944 climate-related abstracts.

They counted any mention of human contribution to warming — explicit or implicit — as part of the “consensus.”

That included:

Papers saying humans caused some warming.

Papers discussing CO₂ as a factor.

Papers mentioning mitigation or impacts in ways that assumed human influence.

By combining all of these, they arrived at the widely cited figure of 97% agreement.

Legates et al. (2013): The 0.3% Figure

Legates re-analyzed the same dataset.

They only counted papers that explicitly stated humans are the primary (>50%) driver of recent warming.

Under this stricter definition, just 0.3% of papers met the criteria.

Why the Huge Difference?

Cook used a broad definition: “humans influence climate in some way.”

Legates used a narrow definition: “humans are the dominant cause.”

Both are technically accurate — they just measure different things.

What Most Scientists Agree On

CO₂ is a greenhouse gas and contributes to warming.

Human activities (burning fossil fuels, land use changes) add CO₂ to the atmosphere.

The debate is not about whether CO₂ has an effect, but whether human emissions are the main driver of recent warming compared to natural variability.

Why This Matters for Local Policy

When Canadian municipalities are asked to adopt costly “net zero” policies under PCP or similar frameworks, the justification is often framed around a supposed 97% consensus. But that number does not mean 97% of scientists say humans are the primary cause. Only a tiny fraction of published papers make that explicit claim.For councils making financial and policy decisions, it is important to recognize this nuance: acknowledging that CO₂ has an influence is not the same as proving that human emissions dominate global climate trends.

-

Local Baselines Instead of Data Collection Overkill

Instead of using ICLEI software or handing over data to corporate partners, municipalities can calculate their own baselines with simple, transparent methods:Use emissions by population and GDP as a straightforward baseline.

Work with your GIS department to review available maps such as WWF and McMaster University’s Carbon Stack Map to measure how much carbon is already stored in your region’s forests, wetlands, soils, and ecosystems.

Calculate the area of each ecosystem in hectares and determine its annual CO₂ absorption.

Subtract this natural absorption from your emissions baseline.

Compare your community’s contribution against the global context:

CO₂ is ~0.04% of Earth’s atmosphere.

Humans are responsible for ~4% of that.

Canada contributes ~1.6% of global human emissions.

Councils can then assess how much taxpayer money is reasonable to spend reducing such a statistically tiny fraction.

Focus on Adaptation, Not Mitigation

Climate changes naturally over interglacial periods, bringing both challenges and benefits. Councils should prioritize adaptation strategies that deliver real, measurable value:Upgrade infrastructure for flood prevention, wildfire resilience, and stormwater management.

Support local food systems and regenerative agriculture.

Plan for expected climate variability rather than chasing speculative global targets.

Natural Climate Solutions Already at Work

Most Canadian ecosystems are already carbon sinks. Municipalities are stewards of these landscapes and should measure and protect them, not ignore them. By recognizing the natural sequestration already occurring in forests, wetlands, grasslands, and soils, councils can show their residents that their communities are part of the solution without costly international schemes.Practical Mitigation if Needed

If a Climate Action Plans or local mitigation is required, focus on solutions that support both the economy and the environment:Rotational grazing to increase soil carbon.

Energy efficiency through normal asset management and infrastructure renewal.

Provincial reporting requirements that already ensure energy-use accountability.

Fiscal Responsibility

Every dollar spent on climate initiatives should be tied to measurable local benefits. Councils should:Set budgets according to the actual percentage of global emissions they are responsible for.

Avoid costly global frameworks with no local accountability.

Focus instead on projects that strengthen community resilience, protect natural assets, and support local prosperity.

Property Rights & Sustainable Development Impacts

-

Habitat I (Vancouver, 1976)

The UN’s first global conference on human settlements, held in Vancouver, set the tone for how “sustainable development” would treat land. Its official declaration stated:“Land cannot be treated as an ordinary asset, controlled by individuals and subject to the pressures and inefficiencies of the market.”

Governments should exercise control over land “in the interest of society as a whole.”

This laid the groundwork for a vision of planning where private ownership is subordinated to collective goals, with governments (and increasingly, global frameworks) shaping how land can be used, transferred, or developed.

Habitat II (Istanbul, 1996) and Habitat III (Quito, 2016) reinforced this by emphasizing urban densification, “right to the city” concepts, and linking housing policy to global climate goals.

Connection to Today’s Policies

PCP, Agenda 21, and ICLEI draw from these same principles, embedding them into municipal zoning, urban planning, and land-use codes.

The idea of limiting suburban growth and promoting densification comes straight from Habitat conference language.

Housing is reframed not as property to be owned and passed on, but as a service to be managed within global frameworks.

Implications for Canadians

Farmland preservation mandates often prevent families from subdividing or selling their own land.

Densification policies reduce local say in how neighborhoods grow, while raising costs.

Combined with corporate investment in housing, these restrictions erode generational wealth and limit ownership opportunities.

Why This Matters

Most municipal councillors and residents don’t know that local zoning changes or “net-zero” land-use policies trace back to UN Habitat conferences. But this history explains why the same themes — densification, restrictions on rural development, and top-down control of land — keep reappearing in Canada’s climate and housing policies. -

One of the least-discussed consequences of global sustainability frameworks like Agenda 21, ICLEI’s PCP program, and the UN’s 2030 Agenda is their impact on property rights and housing affordability. While often presented as harmless “planning” or “guidance,” these frameworks frequently translate into zoning rules, land-use restrictions, and regulatory burdens that directly affect Canadians’ ability to own, manage, and afford property.

Do sustainability goals threaten property rights?

Not always — but they can. Many global frameworks call for farmland preservation, development restrictions, or urban densification. While the stated aim is reducing emissions or preserving ecosystems, the practical impact is that property owners face stricter controls over what they can build, how they can expand, or whether they can subdivide or sell their land.How is this linked to the housing crisis?

Sustainable development programs often push densification in urban cores while restricting rural and suburban growth. This concentrates demand in already expensive housing markets, driving prices even higher. At the same time, large institutional investors such as BlackRock and Vanguard are purchasing housing stock and rental properties at scale, reducing opportunities for individual Canadians to own homes. Together, these policies and market dynamics squeeze supply, inflate prices, and shift ownership toward corporate landlords.What are some examples of impacts on Canadians?

Zoning tied to PCP/ICLEI recommendations that limit suburban expansion and enforce high-density development.

Farmland preservation mandates that restrict generational land transfers or prevent landowners from building.

Urban densification policies that drive up land values while limiting affordable housing supply.

Global investment firms acquiring housing stock while municipalities impose restrictions that disadvantage local buyers.

A growing trend toward “renter societies,” where families are priced out of ownership and locked into permanent tenancy.

How does this differ from traditional local planning?

Historically, municipal planning balanced growth with affordability and community needs. Under sustainable development frameworks, planning is increasingly oriented toward global climate targets, such as “net-zero by 2050” or “15-minute city” models. This shifts the decision-making lens from local affordability and autonomy to external benchmarks — often without community consent.What does KICLEI recommend?

Protect local landowner autonomy: Sustainability policies must involve landowners directly, not impose restrictions from outside frameworks.

Re-balance affordability: Councils should measure how sustainability bylaws affect housing markets and generational wealth transfer.

Transparency: Councils must disclose when zoning or land-use changes are tied to international frameworks like Agenda 21 or PCP.

Challenge corporate capture: Councils should guard against policies that indirectly benefit multinational investors at the expense of local families.

Keep planning local: Environmental stewardship should serve the people who live on the land, not distant NGOs or global funds.

Summary

Global frameworks present land-use restrictions as necessary for climate goals, but in practice they can erode property rights, reduce affordability, and accelerate corporate capture of housing markets. Canada’s housing crisis shows what happens when local planning is subordinated to international agendas and corporate interests. Real sustainability must protect property rights, foster affordable ownership, and keep decision-making in the hands of communities.. -

The PCP framework and its supporting rationale claim that climate programs will “protect public health, support sustainable community development, increase resilience, and reduce vulnerability to social stresses.”

In practice, however, global sustainable development policies have contributed to the opposite outcome in many Canadian communities.

Land Use Restrictions and Housing Scarcity

UN-driven frameworks, beginning with Habitat I and carried through Agenda 21 and ICLEI, assert that “land cannot be treated as an ordinary asset.”

This principle has translated into municipal zoning restrictions, growth boundaries, and densification policies that limit land supply and push up housing costs.

Green building standards, while environmentally appealing, significantly increase construction costs — pricing out working- and middle-class families.

Three Decades of Failed Development Policy

Canada has followed this model for nearly 30 years, embedding “sustainable development” into municipal planning.

Instead of preserving for future generations, the result has been housing scarcity, rising costs, and deepening inequality.

A strategy meant to “protect the future” has too often impoverished the present. It is time to re-examine and reform these policies so they actually deliver both environmental stewardship and affordable living.

Housing Crisis → Social Breakdown

Instead of fostering resilience, these policies have helped create conditions for widespread social stress:Unaffordable Housing: Families are priced out of ownership, creating generational inequality.

Rising Homelessness: Shrinking supply and soaring rents push more people into shelters or onto the streets.

Mental Health Struggles: Housing insecurity drives depression, anxiety, and family instability.

Drug Use & Addiction: Homelessness and despair have fueled the visible drug crisis now present in almost every Canadian city.

The False Promise of Net-Zero Housing Policies

While PCP claims these measures strengthen communities, the reality is:Subsidized “green” developments often benefit luxury developers, not families in need.

Strict zoning codes reduce flexibility for innovative local solutions, like modular housing or incremental builds.

International climate frameworks override local decision-making, leaving councils unable to address the affordability crisis effectively.

What Canadians See Instead

The PCP rationale speaks of resilience and reduced vulnerability. But in cities and towns across Canada, the real picture is stark:Tent encampments in public spaces.

Shelters filled beyond capacity.

A mental health and addiction crisis worsened by housing instability.

The Path Forward

If the true goal is resilient, healthy communities, councils must prioritize:Expanding land supply and loosening zoning barriers.

Allowing housing markets to respond to local needs, not international mandates.

Balancing environmental stewardship with basic human dignity, recognizing that safe, affordable housing is foundational to community well-being.

In short, after three decades of following this global development model, Canadian municipalities have seen worsening affordability, homelessness, and social instability. It is time to rethink and revamp these policies so they truly preserve resources for the future without impoverishing people today.